A looming shortage of Wisconsin nurses has reached its ‘tipping point,’ new hospital workforce report says

Nursing positions are going unfilled in Wisconsin at a rate not seen in at least a decade as the state struggles to replace a rapidly retiring health care workforce, a new report from the state’s hospital association shows.

Although a nursing shortage has been creeping closer for years, the new data shows it’s reached a ‘tipping point’ that should sound alarm bells, said Ann Zenk, vice president of workforce and clinical practice for the Wisconsin Hospital Association.

The association’s annual report, released Tuesday, painted one of the first pictures of what the “Great Resignation” looks like among Wisconsin health care workers.

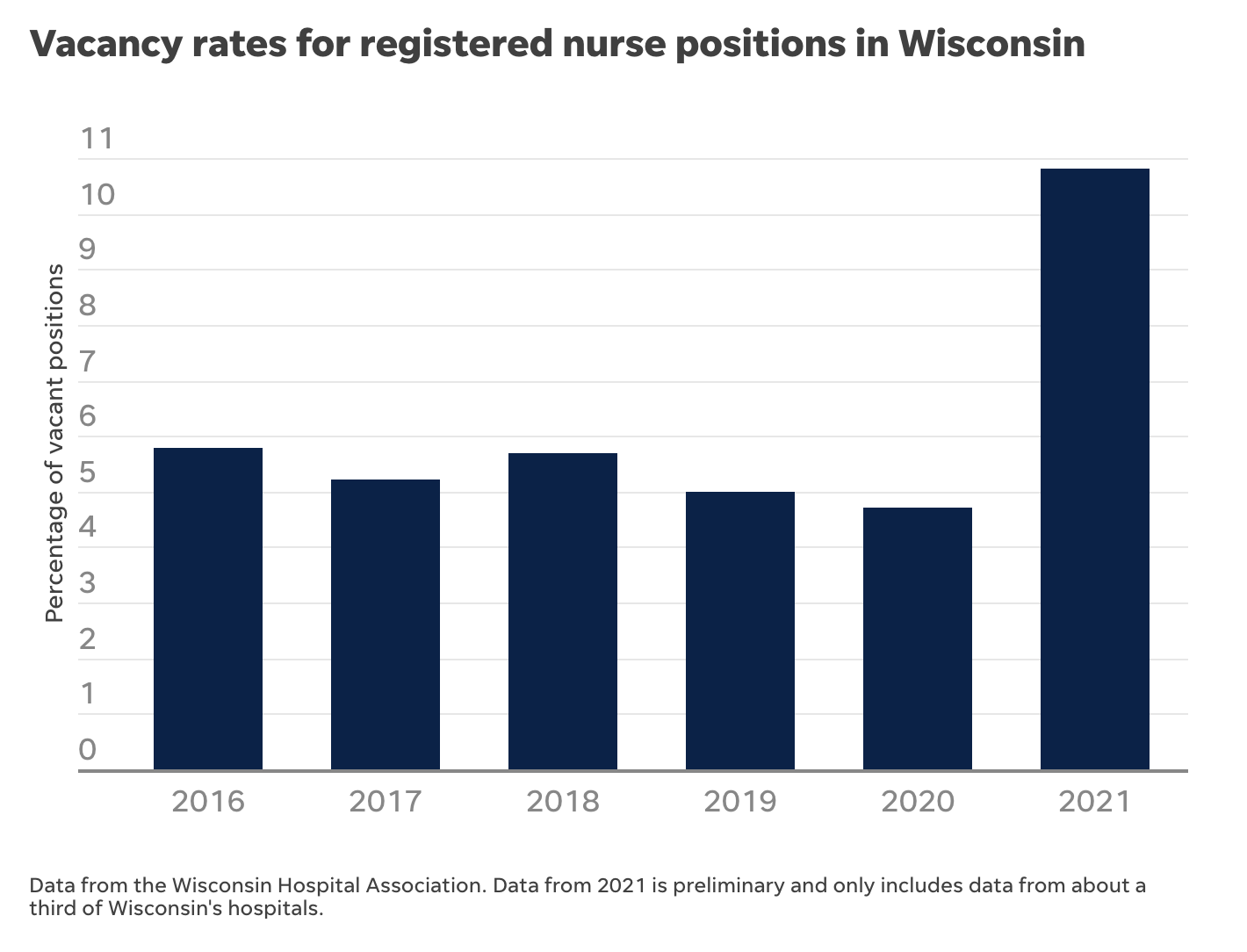

Hospital employees through much of 2020 were largely staying put, according to personnel surveys submitted to the hospital association last year. But those that have submitted data for 2021 — about a third of the state’s hospitals so far — reported vacancy rates last year that were higher than they’d seen since data collection started in 2004.

For example, vacancy rates for registered nurse positions more than doubled from 2020 to 2021, the preliminary data show. There haven’t been double-digit vacancy rates for that role since 2005, according to the report.

“That’s a big benchmark,” Zenk said. “If you’re approaching that, as a hospital employer, you’re thinking, ‘Ooh boy, that’s when it’s starting to feel tough.'”

Registered nurses make up more than half of the state’s health care workforce, but vacancies also are shooting up among 13 of 17 hospital professions, including certified nursing assistants, surgical techs, respiratory therapists, licensed practical nurses, and other front-line employees.

RELATED: Nurses, truck drivers, elementary school teachers are among Wisconsin’s top 10 ‘hottest’ jobs

Turnover rates, typically high among certified nursing assistants and other entry level roles but lower for other more advanced positions, are also spiking: Prior to 2021, about one in 10 registered nurses in Wisconsin changed jobs annually; last year, it was approaching one in five, according to the report.

It’s in line with what’s happening across the country — nearly one in five health care workers have quit their jobs since the pandemic began, according to an October 2021 Morning Consult survey. But it’s an extra burden in Wisconsin, where the state’s population is aging faster and prompting greater demand for health care sercives, while hospital employees in the baby boomer generation are retiring faster than new ones can take their place.

It’s unclear whether people have truly decided to leave health care, Zenk said, or if employment numbers are being redistributed as people move within the health care field searching for the best pay, benefits and work culture.

During the worst COVID-19 surges, Wisconsin hospitals were relying heavily on staffing agencies and traveling nurses to fill gaps and deal with an onslaught of patients. In October 2020, for example, such agencies were advertising nursing positions at more than $4,000 a week.

It’s increasingly possible to work as a travel nurse in or near your own community, Zenk said, a change from when the profession took off in the 1980s.

Some hospitals were offering massive signing bonuses, upwards of $10,000, to compete for the shrinking pool of health care workers.

As nurses continue to pursue employment with staffing agencies, hospitals will have to step up recruitment and retention efforts, the report says.

Pat Raes, a registered nurse at Meriter Hospital in Madison and president of the SEIU Healthcare Wisconsin union, said the situation the report describes is accurate but doesn’t go far enough in detailing solutions that will help nurses and other employees stick around.

Chief among her concerns about nurse retention rates is finding solutions to mental health problems the pandemic has caused or worsened. Nurses saw more death in the last two years than ever before, and they worried even on their time off from work about patients and whether they could be doing more, she said.

But the nursing shortage is forcing many of them to work more instead of taking a break. Just Thursday, Raes said, she got three texts asking if she’d pick up an extra shift.

“Nurses need time to work through a lot of what they’ve gone through,” she said. “And when you’re working extra all the time, it’s hard to work through trauma.”

Whether it’s a call line, formal therapy sessions or helping traumatized employees find a different position in the health care field, Raes said people will need to come together — and be willing to listen to those who work at the bedside — to find a solution to the problem.

With retirements also comes the loss of people to train younger nurses coming into the field. In the state’s last budget cycle, the Administrators of Nursing Education of Wisconsin secured $5 million to help nurses obtain teaching degrees if they commit to teaching for at least three years. (Nurses working in academia earn less than those working in clinical settings.) The group had asked for $10 million for those efforts.

That action may help bulk up nursing faculty, but fell short of what’s needed, Gina Dennik-Champion, executive director of the Wisconsin Nurses Association, said in an email.

Other needs to keep nurses in the field include better salaries, benefits, and job flexibility, reducing the physical demands required in their jobs, and reducing physical and verbal abuse from patients, families, and visitors, Dennik-Champion said.

Solutions the report suggests to increase Wisconsin’s health care workforce include:

- Encouraging Wisconsin students interested in health care to complete their education and training in-state, which raises the likelihood that they’ll work here after graduation.

- Speeding up licensing processes and certification requirements to get employees working in the field faster.

- Leveraging telehealth to reduce strain on bedside caregivers.

- Reducing paperwork and other regulatory requirements that take employees who care for patients away from that patient care.

- Addressing burnout and reducing violence against health care workers in the workplace.

- Making sure patients can move from the hospital to a post-acute care facility when they are ready to do so, to free up hospital staff. .